Early Alphabetic Scripts

The Phoenician script from which the Greek alphabet was adapted is a continuation of early-alphabetic Proto-Canaanite script found across Canaan, which traces its origin to even-earlier Proto-Sinaitic script found in Sinai and Egypt.*

Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite inscriptions† document the progression of early alphabetic script from the iconic form of the Proto-Sinaitic script derived from Egyptian hieroglyphics,‡

to linear§ [composed of simply drawn lines with little attempt at pictorial representation

] Proto-Canaanite script

and its terminal, definitively-Canaanite, but-not-definitively-Phoenician "post Proto-Canaanite" phase that became Phoenician

script.**

11th century BCE Nora Fragment (not Nora Stone) from Sardinia is Proto-Canaanite by date.

10th century BCE Tekke Bowl from Crete looks a lot like the 12th-11th century early alphabetic javelin- or arrowheads

10th century BCE Abda sherd...

*

Rollston (2008):

Within the field of Iron Age Northwest Semitic paleography, the consensus has long been that the Iron Age Phoenician script descended from the early alphabetic script of the Middle Bronze and Late Bronze Ages.

1

Rollston (2016):

First came the Early Alphabetic script (e.g., of the inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol, dating to ca. 18th century BCE), and from this Early Alphabetic script (which continued to be used in the Levantine world for several centuries) came the Phoenician script (in ca. the late 11th century BCE and the early 10th century BCE).

And from the Phoenician script came the Old Hebrew script (in the 9th century BCE) and the Aramaic script (8th century BCE).

2

Hamilton (2006):

Various terms have been employed to describe the earliest West Semitic alphabetic inscriptions and scripts from Egypt, the western Sinai, and Canaan.

[J.] Naveh generally employed

3Proto-Canaanite,

while [F. M.] Cross usually used Old Canaanite

as synonymous terms for this script tradition and its earliest epigraphs.

[B.] Sass used the designation Proto-Sinaitic,

a term initiated by [W. F.] Albright, for the texts and scripts from the Sinai and Proto-Canaanite

for those from Palestine.

Those two terms were similarly employed by [D.] Pardee and [A.] Lemaire.

[B. E.] Colless coined the term proto-alphabetic

for both (in part to distinguish them from ones he considered syllabic or syllabic-logographic).

[M.] O’Connor usually used Northern Linear (Canaanite).

[J. C.] Darnell et al. preferred early alphabetic

in part to find a more neutral designation that would include two new West Semitic texts found at Wadi el-Ḥol in Egypt.

Colless (2014):

In my opinion the frequently used terms “Protosinaitic” and “Protocanaanite” are now obsolete; the former was a subset of the latter, and yet it is incorrectly applied to all protoalphabetic inscriptions, even though it is obviously applicable only to the Sinai examples.

4

†

Carr (2011):

Most, but not all, epigraphic finds from the tenth century are brief labels or word

fragments. Many indicate possession or the destination of the contents of a given

container or object:

[b]n ḥnn on a bowl rim...at Tel Batash [Timnah]...,

ḥnn carved on a gaming board at Beth Shemesh...,

[]n ḥmr[] in Khirbet Rosh Zayit...,

lʾdnn in ink on an ostracon at Tell el-Fara,

lnmš on a jar handle...at Tel Amal...,

and three inscriptions...at ...Tel Rehov:

lnḥ[?] incised ona storage jar...,

mʿ—ʿm on the collar of a jar, and lšq?nmš ("to the cupbearer Nimshi"?).

5

Millard (2011):

Discoveries of written documents in the Holy Land are always noteworthy, especially those from the Eleventh and Tenth Centuries BC. From those centuries there are very few examples indeed.

There are only two of any length. The Gezer Calendar is well known...and generally dated to about 925 BC. A more recent find is the alphabet...unearthed at Tel Zayit.... Apart from these there are only personal names scratched on a stone and on potsherds that can be placed approximately in the Tenth Century, the period of the reigns of David and Solomon.

They are part of a gaming board from Beth Shemesh, and sherds from Tell eṣ-Ṣafī (probably Gath), from Tel ‘Āmal, near Beth-Shan, from Timnah [Tel Batash], and from Khirbet Rosh Zayit, near Kabul in the north, which might be Phoenician.

Earlier than that, there are equally few documents assigned to the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries: little more than names on potsherds from Khirbet Raddana, Lachish, Manaḥat and Qubur el-Walayda, the ‘Izbet Ṣarṭah ostracon bearing several lines faintly scratched, one legible as an abc, a hardly legible ink-written ostracon from Beth Shemesh, names incised on bronze arrowheads and a name incised on a bronze bowl found at Kefar Veradim in the north, which may be Phoenician.

The scarcity of inscriptions from the Holy Land in the Twelfth to Tenth Centuries BC and the relative rarity of Hebrew epigraphic remains from the Ninth Century when compared with the Eighth to Sixth Centuries continues to arouse discussion.

6

‡

Goldwasser (2011):

Almost all signs of the new alphabet letters in Sinai have clear prototypes in the Middle Kingdom Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions that surround the [Serabit el Khadem] mines and in a few other inscriptions found on the roads to the mines.

7

Goldwasser (2010):

There are some very specific connections between the Middle Kingdom Egyptian hieroglyphs in Sinai and the new script.

There is one hieroglyph that appears...only in Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions in the Sinai during the Middle Kingdom.

... The sign looks like a striding man with bent, upraised arms....

In the Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions in Sinai, this sign...probably means something like “foreman.”

This hieroglyph appears dozens of times in Egyptian Middle Kingdom inscriptions at Serabit.

(Its phonetic reading in Egyptian in this specific use in Sinai, however, is unknown.)

This hieroglyph is rare even in later New Kingdom Egyptian inscriptions at Serabit.

And it hardly ever appears anywhere else in Egypt.

A letter in the new Proto-Sinaitic alphabet looks very much like this Middle Kingdom Egyptian hieroglyph.

The Proto-Sinaitic sign...almost certainly stems directly from the Egyptian hieroglyph.

The Canaanites at Serabit probably connected this pictogram, which they saw everywhere at the site, with a loud call or order emitted by an official when he raised his hands to assemble the people, a typical shout such as Hoy! (also known in Biblical Hebrew), which may be the origin of the letter h in the Proto-Sinaitic script..

8

§

Finkelstein, Sass (2013):

The meagre documentation shows that [in the Late Bronze Age II–III] the [Proto-Canaanite] alphabet has undergone a partial linearization compared with the Sinai and Wadi el-Hol prototypes:

For instance, the alep lost its bull’s-head shape, the ʿayin is circular rather than lentoid or eye-shaped, and the resh lost its human-head form.

Yet some LB II–III letters are still quite close to the earliest pictographs, such as the bet of the Lachish bowl fragment with exact comparisons at Wadi el-Hol, and the he of the Nagila sherd and Lachish bowl fragment resembling the Sinai and Wadi el-Hol forms.

9

**

Wikipedia:

The name Phoenician is by convention given to inscriptions beginning around 1050 BC, because Phoenician, Hebrew, and other Canaanite dialects were largely indistinguishable before that time.

10

Wikipedia:

Proto-Canaanite is the name given to...a hypothetical ancestor of the Phoenician script before some cut-off date, typically 1050 BCE.... No extant "Phoenician" inscription is older than 1000 BCE.

11

1.

Note: Christopher A. Rollston, The Phoenician Script of the Tel Zayit Abecedary and Putative Evidence for Israelite Literacy,

in Literate Culture and Tenth-Century Canaan: The Tel Zayit Abecedary in Context, ed. Ron Tappy and P. Kyle McCarter (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2008), https://www.academia.edu/474482/The_Phoenician_Script_of_the_Tel_Zayit_Abecedary_and_Putative_Evidence_for_Israelite_Literacy (accessed ...),

p. 72.

2.

Note: Christopher A. Rollston, The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions 2.0: Canaanite Language and Canaanite Script, Not Hebrew,

Rollston Epigraphy, 10 December 2016, http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=779 (accessed ...).

3. Note: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,W.Sem%20Alphabet,1.pdf [pp. 1-64] (accessed ...), p. 4.

4.

Note: Brian E. Colless, The Origin of the Alphabet: An Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis,

Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014), https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/32623054.pdf [pp. 71-104] (accessed ...),

p. 72. n. 2.

5. Note: David M. Carr, The Formation of the Hebrew Bible: A New Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), https://books.google.com/books?id=pPy3gXJDI7AC&pg=PA375 (accessed ...), p. 375.

6.

Note: Alan R. Millard, The Ostracon from the Days of David Found at Khirbet Qeiyafa,

Tyndale Bulletin 62:1 (2011), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288307959_The_ostracon_from_the_days_of_david_found_at_khirbet_qeiyafa,

p. 1.

7.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, The Advantage of Cultural Periphery: The Invention of the Alphabet in Sinai (circa 1840 B.C.E),

in Culture Contacts and the Making of Cultures: Papers in Homage to Itamar Even-Zohar, ed. Rakefat Sela-Sheffy and Gideon Toury (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University / Unit of Culture Research, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/37555692/2011_The_Advantage_of_Cultural_Periphery_The_Invention_of_the_Alphabet_in_Sinai_circa_1840_B_C_E_In_Culture_Contacts_and_the_Making_of_Cultures_Papers_in_Homage_to_Itamar_Even_Zohar_Eds_R_Sela_Sheffy_and_G_Toury_Tel_Aviv_Tel_Aviv_University_Unit_of_Culture_Research_251_316 [pp. 251–316] (accessed ...),

p. 265.

8.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, How the Alphabet was Born from Hieroglyphs,

Biblical Archaeology Review [BAR] (Biblical Archaeology Society [BAS]) 36:2 (March/April 2010),

https://www.academia.edu/6916402/Goldwasser_O_2010_How_the_Alphabet_was_Born_from_Hieroglyphs_Biblical_Archaeology_Review_36_2_March_April_40_53_Award_Best_of_BAR_award_for_2009_2010_Discussion_with_Anson_Rainey_http_www_bib_arch_org_scholars_study_alphabet_asp_ [pp. 38-51] (accessed ...),

p. 43.

9.

Note: Israel Finkelstein and Benjamin Sass, The West Semitic Alphabetic Inscriptions, Late Bronze II to Iron IIA: Archeological Context, Distribution and Chronology,

Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 2.2 (2013), https://www.academia.edu/5300339/2013_Finkelstein_I_and_Sass_B_The_West_Semitic_alphabetic_inscriptions_Late_Bronze_II_to_Iron_IIA_Archeological_context_distribution_and_chronology_Hebrew_Bible_and_Ancient_Israel_2_2_149_220 [pp. 149-220] (accessed ...),

p. 173.

10.

Note: Wikipedia, s.v. Phoenicia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phoenicia#Alphabet (accessed ...).

11.

Note: Wikipedia, s.v. Proto-Canaanite alphabet,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Canaanite_alphabet (accessed ...).

Two Abecedaries

A couple of (slightly-out-of-order) abecedaries establish correlation between the recognizable glyphs of the later, "post Proto-Canaanite" (pre-

Phoenician) script on the first, and less-recognizable forms of an earlier instance of Proto-Canaanite script on the second.

Tel Zayit Abecedary [2005] (10th [9th] Century BCE)

Image source: Alchetron. Additional images: The Zeitah Excavations.

| Transcription | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

𐤀 𐤁 𐤂 𐤃 𐤅 𐤄 𐤇 𐤆 𐤈 𐤉 𐤋 𐤊 𐤌 𐤍 [𐤎] [𐤐] [𐤏] [𐤑] [𐤒] [𐤓] 𐤔 [𐤕] |

(1) ʾ b g d w h ḥ z ṭ y l k m n [s] [p] [ʿ] [ṣ] (2) [q] [r] š [t] |

Transliteration source: Tappy, McCarter, Lundberg, Zuckerman (2006).2

Notes

Wikipedia:

The Zayit Stone is a 38-pound (17 kg) limestone boulder discovered on 15 July 2005 at Tel Zayit (Zeitah) in the Guvrin Valley.

... It is the earliest known example of the complete Phoenician, or Paleo-Hebrew, alphabet.

... There has been some disagreement as to whether the inscription should be associated with the coastal (Phoenician) or highland (Hebrew) cultural sphere. Consequently, there has been debate on whether the letters should be described as

3Paleo-Hebrew

, as Phoenician

, or more broadly as South Canaanite.

Center for Online Judaic Studies [COJS]:

At Tel Zayit, archaeologists unearthed a limestone boulder embedded in a wall.

The letters of the Hebrew alphabet were inscribed on it in their traditional order. The stone was part of a wall dated to the 10th century BCE, leading to the conclusion that this is the earliest known specimen of the Hebrew alphabet.

4

Biblical Archaeology Society (2020):

[Christopher] Rollston continues his analyses on some other contenders for the oldest Hebrew inscription. He finds the Tel Zayit Abecedary to be fully Phoenician script, despite the excavation epigrapher claiming that the abecedary indicates the transition between the scripts.

5

Parker (2013, 2018):

The Tel Zayit abecedary was recovered in 2005 during the excavations of Tel Zayit led by R. E. Tappy. It was found in Tel Zayit Local Level III, which the excavators date to the tenth century BCE.

6

Aḥituv, Mazar (2013):

An abecedary from Tel Zayit, incised on a large stone mortar in secondary use in a wall of a building was dated to the tenth century BCE.

7

Finkelstein, Sass (2013):

Undifferentiated non-Hebrew, late Iron IIA1 [ca. 880-840/830].

... While the script is quite close to that of the unstratified Gezer calendar,

the diagnostic mem and nun of Tel Zayit are far more developed,

practically identical to their counterparts in the considerably later Phoenician “Baal Lebanon” bowls,

and earliest Greek alphabets.

8

Sass, Finkelstein (2016):

This Philistian inscription was discovered in a context that probably dates to late Iron IIA/1.

... According to stratified inscriptions, Proto-Canaanite was still the only script-style in use in early Iron IIA [ca. 940–880], which would exclude such a dating for cursive-inspired Tel Zayit.

... We consider the stratigraphic situation of the Tel Zayit abecedary reasonably established in late Iron IIA/1, absolute dating towards 850....

The level-headed mem lasted for a long time—well into the eighth century (or even seventh).

...When more Tel Zayit letters are considered, such as the nearly legless dalet, “crescent on pole” waw and tall zayin, the time-range may end earlier, say a little after 800, or still within late Iron IIA/2 [ca. 840/830-780/770].

9

1. Image:

2.

Transliteration: Ron E. Tappy, P. Kyle McCarter, Marilyn J. Lundberg, and Bruce Zuckerman, An Abecedary of the Mid-Tenth Century B.C.E. from the Judaean Shephelah,

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) 344 (November 2006), https://www.academia.edu/9206107/An_Abecedary_of_the_Mid_Tenth_Century_B_C_E_from_the_Judaean_Shephelah [pp. 5-46] (accessed ...),

p. 26.

3.

Note: Wikipedia, s.v. Zayit Stone,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zayit_Stone (accessed ...).

4.

Note: Center for Online Judaic Studies [COJS], Tel Zayit Inscription, 10th century BCE,

http://cojs.org/tel_zayit_inscription-_10th_century_bce/ (accessed ...).

5.

Note: Biblical Archaeology Society Staff, The Oldest Hebrew Script and Language,

Bible History Daily (Biblical Archaeology Society [BAS]), 03 July 2020, https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-artifacts/inscriptions/the-oldest-hebrew-script-and-language/ (accessed ...).

6.

Note: Heather Dana Davis Parker, The Levant Comes of Age: The Ninth Century BCE Through Script Traditions

(PhD diss., Johns Hopkins University, October 2013, Revised 31 May 2018), https://www.academia.edu/36755960/PARKER_LEVANT_COMES_OF_AGE_PARTI_05312018_docx (accessed ...),

p. 123, n. 538.

7.

Note: Shmuel Aḥituv and Amihai Mazar, The Inscriptions from Tel Reḥov and their Contribution to the Study of Script and Writing during Iron Age IIA,

in See, I will bring a scroll recounting what befell me

(Ps 40:8): Epigraphy and Daily Life from the Bible to the Talmud, ed. Esther Eshel and Yigal Levin (Vandehoeck & Rupprecht, 2013), https://www.academia.edu/8051985/Ahituv_S_and_Mazar_A_The_Inscriptions_from_Tel_Reḥov_and_their_Contribution_to_Study_of_Script_and_Writing_during_the_Iron_Age_IIA [pp. 39-203] (accessed ...),

p. 56.

8.

Note: Israel Finkelstein and Benjamin Sass, The West Semitic Alphabetic Inscriptions, Late Bronze II to Iron IIA: Archeological Context, Distribution and Chronology,

Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 2.2 (2013), https://www.academia.edu/5300339/2013_Finkelstein_I_and_Sass_B_The_West_Semitic_alphabetic_inscriptions_Late_Bronze_II_to_Iron_IIA_Archeological_context_distribution_and_chronology_Hebrew_Bible_and_Ancient_Israel_2_2_149_220 [pp. 149-220] (accessed ...),

pp. 166-167.

9.

Note: Benjamin Sass and Israel Finkelstein, The Swan-Song of Proto-Canaanite in the Ninth Century BCE in light of an Alphabetic Inscription from Megiddo,

Semitica Et Classica [SEC] International Journal of Oriental and Mediterranean Studies 9 (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2016), https://www.academia.edu/38692710/B_Sass_I_Finkelstein_The_Swan_Song_of_Proto_Canaanite_in_the_Ninth_Century_BCE_in_light_of_an_Alphabetic_Inscription_from_Megiddo_Semitica_et_Classica_9_2016_ [pp. 19-42] (accessed ...),

pp. 30, 32-33.

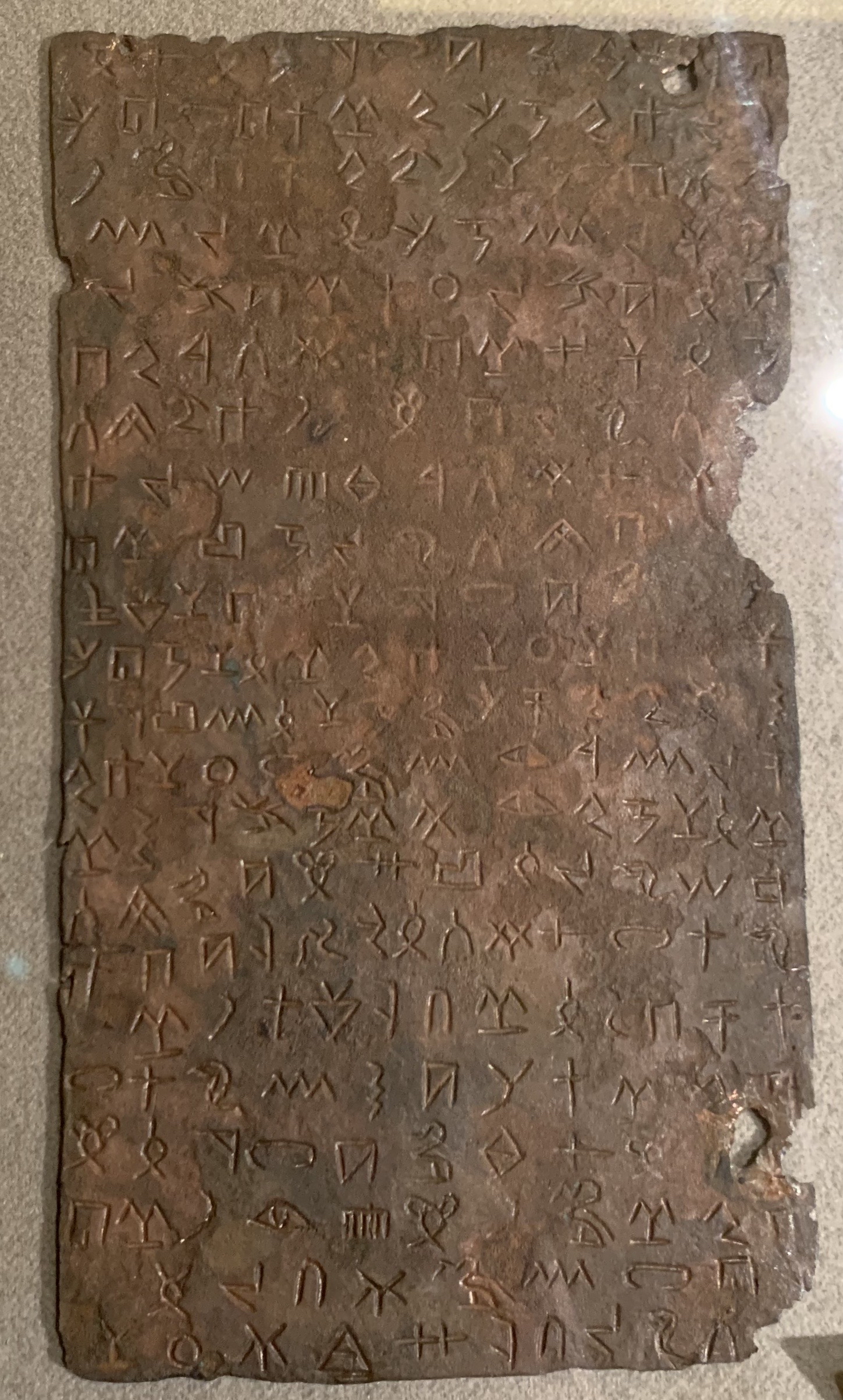

Izbet Sartah Abecedary [1976] (12th-11th [10th-9th] Century BCE)

Izbet Sartah Ostrakon; BAS Library. Source: Minkoff (1997).1

Izbet Sartah Abecedary; Aaron Demsky. Source: Demsky (2015).2

Izbet Sartah Abecedary; Frank M. Cross. Source: Cross (1980).3

Izbet Sartah Abecedary; Benjamin Sass. Source: Sass, Garfinkel, Hasel, Klingbeil (2015).4

Izbet Sartah Abecedary. Source: Colless (n.d.).5

| Transcription | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

𐤀𐤋𐤌𐤃 𐤀𐤕𐤉𐤕 𐤀𐤏(𐤉𐤍) 𐤊 𐤕𐤕𐤍 𐤏(𐤉𐤍) 𐤓𐤇 𐤀𐤕 𐤁 𐤀𐤆[𐤍 𐤁 𐤏]𐤈 𐤏𐤋 𐤈𐤈 𐤑𐤌𐤒 𐤌𐤓𐤒 𐤓𐤏 𐤅 𐤐 𐤁 𐤍𐤇 𐤂 𐤀𐤕 𐤋 𐤄𐤃 𐤆𐤒𐤍 𐤏𐤕 𐤏(𐤉𐤍) 𐤋 𐤀(𐤋𐤐) 𐤇𐤋𐤃 𐤏𐤋𐤌 𐤀𐤁𐤂𐤃𐤄𐤌𐤅𐤇𐤆𐤈𐤉𐤊𐤋𐤍|𐤎𐤐𐤏𐤑𐤒𐤓𐤔𐤕 |

ʾlmd ʾtyt ʾʿ(yn) k ttn ʿ(yn) rḥ ʾt b ʾz[n b ʿ]ṭ ʿl ṭṭ ṣmq mrq rʿ w p b nḥ g ʾt l hd zqn ʿt ʿ(yn) l ʾ(lp) ḥld ʿlm ʾbgdhmwḥzṭykln|spʿṣqršt |

I am learning the letter-forms (marks of signs). I am seeing that the eye gives the breath of a letter (sign) into the ea[r by a styl]us on clay (that is) dried (and) polished. r-‘- r- p/ga bi na ḥa gi has come to the splendour of old age (zaqini ‘iti??). See, I shall be seen for a thousand lifetimes of the world. ʾ B G D H M W Ḥ Z Ṭ Y K L N | S P ʿ Ṣ Q R Š T |

Transliteration and translation source: Colless (n.d.):

Note that this is

6

Colless (2020):

work in progress

and is continually being modified.A scribe reflects on how this writing system works.

7

Notes

Broyles (n.d.):

During...the excavation [of ‘Izbet Sartah], two fragments from a large earthenware jar were found at the bottom of a storage pit. The fragments fitted together, and upon close examination, proved to bear writing.

... [The find] bridges a gap in our knowledge of the development of writing.

The earliest system of writing, dating around 3500 B.C., was pictographic.

... Eventually it was replaced by alphabetic writing.

The ‘Izbet Sartah inscription dates from the time when writing was undergoing this fundamental change.

Pictographic elements are present in several of the letters.

The aleph is still drawn like an ox’s head, horns to the left. Kaf is drawn like a hand with three (or five?) fingers.

... Aaron Demsky, summing up the significance of the find, says that it is

8the missing link in the evolution of the alphabet from Proto-Canaanite to the Old Hebrew and Phoenecian scripts.

Some of the letters hark back to the older alphabets while others anticipate later forms.

Naveh (1978):

The ostracon recently found at ʿIzbet Sartah...is the largest inscribed item among the scant late Proto-Canaanite inscriptions dating from ca. 1300-1050 B.C.

... There are five lines... the letters of [line] 1 [when the ostracon is inverted]...form an abecdary.

The letters of [lines] 2-5...do not seem to comprise a text in any Semitic language.

For the time being the ostracon can be best be described as the scratchings of some semi-literate person.

9

Colless (n.d.):

An...attempt to find continuous meaning in the first four lines has been made by [A.] Dotan;

initially [M.] Kochavi and [A.] Demsky tried this approach, but both eventually decided that it was simply an exercise in writing the letters of the alphabet.

... The message obtained from [my] proposed interpretation for lines 1-3 seems fairly plausible: a student (apparently of mature age) has been learning to write with the alphabet, and muses over the art of writing on ostracon-tablets.

If line 4 is a continuation of this, we might suppose that the scribe's name is embedded in the long uninterrupted sequence of signs (bnḥg could be

10son of Haggi

).

Millard (2011):

Assigned to the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries.

11

Azevedo (1994): ʿIzbet Sartah 12th BC.12

Finkelstein, Sass (2013):

Late Iron I [ca. mid 1000s-940] to early Iron IIA [ca. 940–880]. Some of the inscriptions [e.g., the ʿIzbet Ṣarṭah ostracon] are still wholly Proto-Canaanite.

13

1.

Image: Harvey Minkoff, As Simple as ABC,

Bible Review (Biblical Archaeology Society [BAS]) 13:2 (April 1997), https://www.baslibrary.org/bible-review/13/2/11.

2.

Drawing: Aaron Demsky, A Proto - Canaanite Abecedary Dating from the Period of the Judges and its Implications for the History of the Alphabet,

Tel Aviv Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 4:1-2 (2011), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/033443577788497786?journalCode=ytav20 (accessed ...),

p. 14, Fig. 1: Proto-Canaaite abecedary from Izbet Ṣarṭah.

3.

Drawing: Frank Moore Cross, Newly Found Inscriptions in Old Canaanite and Early Phoenician Scripts [1980],

in Leaves from an Epigrapher's Notebook: Collected Papers in Hebrew and West Semitic Palaeography and Epigraphy (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2003), https://brill.com/view/book/9789004369887/BP000033.xml (accessed ...),

p. 221, Figure 32.6: A tracing of the ʿIzbet Ṣarṭah sherd.

4.

Drawing: Benjamin Sass, Yosef Garfinkel, Michael G. Hasel, Martin G. Klingbeil, The Lachish Jar Sherd: An Early Alphabetic Inscription Discovered in 2014,

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) 374 (November 2015), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316977263_2015_B_Sass_Y_Garfinkel_MG_Hasel_and_MG_Klingbeil_The_Lachish_Jar_Sherd_An_Early_Alphabetic_Inscription_Discovered_in_2014_Bulletin_of_the_American_Schools_of_Oriental_Research_374_233-245 (accessed ...),

p. 240, Fig. 19: ʿIzbet Ṣarṭah ostracon (Sass 1988: Fig. 175).

5.

Image: Brian E. Colless, The Izbet Sartah Ostrakon: Musings of a Student Scribe,

Collesseum: A Museum-Theatre for Scripts (n.d.), https://sites.google.com/site/collesseum/abgadary (accessed ...).

6. Transliteration and translation: Colless (n.d.), Interpretation of the Text.

7.

Note: Brian E. Colless, Honey Bees at Ancient Rehob,

CRYPTCRACKER, 07 October 2020, http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2020/10/ancient-rehob-and-its-apiary.html (accessed ...).

8.

Image: Stephen Broyles, The Alphabet from ‘Izbet Sartah: The State of Writing in the Period of the Judges,

The Andreas Center (n.d.), https://www.andreascenter.org/Articles/Alphabet.htm (accessed ...).

9.

Note: Joseph Naveh, Some Considerations on the Ostracon from 'Izbet Ṣarṭah,

Israel Exploration Journal [IEJ] 28:1/2 (1978), https://www.jstor.org/stable/27925644?seq=1 (accessed ...),

p. 31.

10. Note: Colless (n.d.).

11.

Note: Alan R. Millard, The Ostracon from the Days of David Found at Khirbet Qeiyafa,

Tyndale Bulletin 62:1 (2011), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288307959_The_ostracon_from_the_days_of_david_found_at_khirbet_qeiyafa,

p. 2.

12.

Note: Joaquim Azevedo, The Origin and Transmission of the Alphabet

(1994), Master's Theses, 28, https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=theses (accessed ...),

p. 105.

13.

Note: Israel Finkelstein and Benjamin Sass, The West Semitic Alphabetic Inscriptions, Late Bronze II to Iron IIA: Archeological Context, Distribution and Chronology,

Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 2.2 (2013), https://www.academia.edu/5300339/2013_Finkelstein_I_and_Sass_B_The_West_Semitic_alphabetic_inscriptions_Late_Bronze_II_to_Iron_IIA_Archeological_context_distribution_and_chronology_Hebrew_Bible_and_Ancient_Israel_2_2_149_220 [pp. 149-220] (accessed ...),

pp. 157, 159.

Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions

1.

Note: Israel Finkelstein and Benjamin Sass, The West Semitic Alphabetic Inscriptions, Late Bronze II to Iron IIA: Archeological Context, Distribution and Chronology,

Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 2.2 (2013), https://www.academia.edu/5300339/2013_Finkelstein_I_and_Sass_B_The_West_Semitic_alphabetic_inscriptions_Late_Bronze_II_to_Iron_IIA_Archeological_context_distribution_and_chronology_Hebrew_Bible_and_Ancient_Israel_2_2_149_220 [pp. 149-220] (accessed ...),

p. 153, n. 16: We do not deal here with the Sinai and Wadi el-Hol inscriptions, nor...pre-LB II alphabetic inscriptions in Canaan

;

p. 180: Late Bronze II: 13th century.

Schumm (2014):

Before the alphabet was invented, early writing systems had been based on pictographic symbols known as hieroglyphics, or on cuneiform wedges, produced by pressing a stylus into soft clay.

Because these methods required a plethora of symbols to identify each and every word, writing was complex and limited to a small group of highly-trained scribes.

Sometime during the second millennium B.C. (estimated between 1850 and 1700 B.C.), a group of Semitic-speaking people adapted a subset of Egyptian hieroglyphics to represent the sounds of their language.

This Proto-Sinaitic script is often considered the first alphabetic writing system, where unique symbols stood for single consonants (vowels were omitted). Written from right to left and spread by Phoenician maritime merchants who occupied part of modern Lebanon, Syria and Israel, this consonantal alphabet—also known as an abjad—consisted of 22 symbols simple enough for ordinary traders to learn and draw, making its use much more accessible and widespread.

1

Wilford (1999):

Alphabetic writing was revolutionary in a sense comparable to the invention of the printing press much later.

Alphabetic writing emerged as a kind of shorthand by which fewer than 30 symbols, each one representing a single sound, could be combined to form words for a wide variety of ideas and things. This eventually replaced writing systems like Egyptian hieroglyphics in which hundreds of pictographs, or idea pictures, had to be mastered.

... Only a scribe trained over a lifetime could handle the many different types of signs in the formal writing. So these people adopted a crude system of writing within the Egyptian system, something they could learn in hours, instead of a lifetime. It was a utilitarian invention for soldiers, traders, merchants.

2

Goldwasser (2010):

The invention of the alphabet ushered in what was probably the most profound media revolution in history.

Earlier writing systems, like Egyptian hieroglyphic and Mesopotamian cuneiform with its curious wedge-shaped characters, each required a knowledge of hundreds of signs.

To write or even to read a hieroglyphic or cuneiform text required familiarity with these signs and the complex rules that governed their use.

By contrast, an alphabetic writing system uses fewer than 30 signs, and people need only a few relatively simple reading rules that associate these signs with sounds.

3

Rollston (2016):

The inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol can be dated to ca. the 18th century BCE.

... The best terms [for the script of these inscriptions] are “Early Alphabetic,” or “Canaanite.” Some prefer the term “Proto-Sinaitic Script.”

... The script of these inscriptions...is the early ancestor of [the distinctive national scripts—Phoenician, Hebrew, Aramaic, Moabite, Ammonite, and Edomite].

... From this Early Alphabetic script (which continued to be used in the Levantine world for several centuries) came the Phoenician script (in ca. the late 11th century BCE and the early 10th century BCE).

And from the Phoenician script came the Old Hebrew script (in the 9th century BCE) and the Aramaic script (8th century BCE).

4

Rollston (2021):

In terms of the earlier history of the alphabet, especially as reflected in the Early Alphabetic inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol, the most elegant and convincing date (based especially on things such as the palaeographic similarities between Middle Egyptian Hieroglyphic and Hieratic vis a vis the Early Alphabetic inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol as well as the dating of Egyptian inscriptions at these same sites, etc.) is often contended to be the chronological horizon of the 18th century BCE.

... Someone might attempt to push the data down chronologically and argue for the 17th century BCE for the inscriptions of Serabit and el-Hol.

Conversely, it is worth emphasizing that as for the date of the invention of Early Alphabetic, Orly Goldwasser has argued for a date of ca. 1840 BCE, an earlier date than has often been embraced.

Frank Moore Cross dated the invention of the alphabet to ca. 18th century BCE and Joseph Naveh dated the invention of the alphabet to ca. 1700 BCE.

In essence, therefore, this chronological horizon (19th or 18th century) has been the consensus view (although occasionally a [much] lower date will be proposed [e.g., Sass], but the data continue to mount against that view).

5

Wikipedia:

The Proto-Sinaitic script of Egypt has yet to be fully deciphered.

However, it may be alphabetic and probably records the Canaanite language.

... This Semitic script adapted Egyptian hieroglyphs to write consonantal values based on the first sound of the Semitic name for the object depicted by the hieroglyph (the "acrophonic principle").

So, for example, the hieroglyph per ("house" in Egyptian) was used to write the sound [b] in Semitic, because [b] was the first sound in the Semitic word for "house", bayt.

The script was used only sporadically, and retained its pictographic nature, for half a millennium....

6

Rollston (2016):

The words in the inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol are found in lots of Semitic languages, not just one.

... (1) the inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol are written in the Early Alphabetic script (also called “Canaanite” and “Proto-Sinaitic”)...and

(2) the language of the inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol is not the Hebrew, or Phoenician, or Aramaic language, but rather it is a West Semitic language or dialect that is best termed “Canaanite.”

7

1.

Note: Laura Schumm, Who created the first alphabet?

History.com, 6 Aug 2014, Updated 22 Aug 2018, https://www.history.com/news/who-created-the-first-alphabet (accessed ...).

2.

Note: John Noble Wilford, Discovery of Egyptian Inscriptions Indicates an Earlier Date for Origin of the Alphabet,

New York Times, 13 November 1999, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/national/science/111499sci-alphabet-origin.html (accessed ...).

3.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, How the Alphabet was Born from Hieroglyphs,

Biblical Archaeology Review [BAR] (Biblical Archaeology Society [BAS]) 36:2 (March/April 2010),

https://www.academia.edu/6916402/Goldwasser_O_2010_How_the_Alphabet_was_Born_from_Hieroglyphs_Biblical_Archaeology_Review_36_2_March_April_40_53_Award_Best_of_BAR_award_for_2009_2010_Discussion_with_Anson_Rainey_http_www_bib_arch_org_scholars_study_alphabet_asp_ [pp. 38-51] (accessed ...),

p. 40.

4.

Note: Christopher A. Rollston, The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions 2.0: Canaanite Language and Canaanite Script, Not Hebrew,

Rollston Epigraphy, 10 December 2016, http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=779 (accessed ...).

5.

Note: Christopher A. Rollston, Tell Umm el-Marra (Syria) and Early Alphabetic in the Third Millennium: Four Inscribed Clay Cylinders as a Potential Game Changer,

Rollston Epigraphy, 16 April 2021, http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=921 (accessed ...).

6.

Note: Wikipedia, s.v. History of the alphabet,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_alphabet#Semitic_alphabet (accessed ...),

Semitic alphabet.

7.

Note: Christopher A. Rollston, The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions 2.0: Canaanite Language and Canaanite Script, Not Hebrew,

Rollston Epigraphy, 10 December 2016, http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=779 (accessed ...).

Serabit el-Khadim Inscriptions [1905] (19th-16th Century BCE, ca. 1850-1500)

Wikipedia:

In the winter of 1905, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie and his wife Hilda Petrie (née Urlin) were conducting a series of archeological excavations in the Sinai Peninsula.

During a dig at Serabit el-Khadim, an extremely lucrative turquoise mine used during between the Twelfth and Thirteenth Dynasty and again between the Eighteenth and mid-Twentieth Dynasty, Sir Petrie discovered a series of inscriptions at the site's massive invocative temple to Hathor, as well as some fragmentary inscriptions in the mines themselves.

... In 1916, Alan Gardiner...published his own interpretation of Petrie's findings.

... [Gardiner] was able to assign sound values and reconstructed names to some of the letters by assuming they represented what would later become the common Semitic abjad.

... His model allowed an often recurring word to be reconstructed as lbʿlt, meaning "to Ba'alat" or more accurately, "to (the) Lady" – that is, the "lady" Hathor.

... Gardiner's hypothesis allowed researchers to connect the letters of the inscriptions to modern Semitic alphabets.

1

Haring (2020):

In an article published in 1916, Sir Alan Gardiner gave his interpretation of the inscriptions.

... Just as in later Semitic alphabets, the individual signs stood for single consonants.

... Several more characters could be explained in this way, but the phonetic reading and graphic derivation of others remain highly problematic to this day.

Even the total number of different signs in this writing system remains unclear.

2

Haring (2020):

[B.] Sass lists 22 signs with phonetic identifications, five of them with a question-mark, beside several unidentified and unclear signs.

The quasi-absence of g(imel) is especially disturbing.

Its single occurrence in Sinai 367 (as supposed by Sass) is not convincing and was identified as y(od) by Hamilton.

The latter author distinguishes 31 different signs in the Sinai corpus, not counting g(imel) and ǵ(ain), and assuming that seven consonants (b, d, h, y, n, ṣ, θ) were each expressed by two different signs.

3

Goldwasser (2011):

About 30 early alphabetic inscriptions have been found in Sinai. Most of them come from the areas of the mines (some were written inside the mines) in Serabit el Khadem, and a few have been found on the roads leading to the mines.

... In Egypt itself, on the other hand, two lines of alphabetic inscription have been found to date [Wadi el-Ḥôl].

... Another tiny ostracon was found in the Valley of the Queens and should probably be dated to the New Kingdom.

... In the entire region of Canaan and Lebanon, less than a dozen in-scriptions dating from the 17th to the 13th centuries B.C.E. have been discovered. Moreover, they were found at different sites far apart from each other. There is hardly a site that has yielded more than a single inscription.

... A unique situation was created in Sinai where some illiterate (although surely not

4primitive

or less advanced

) workers with strong Canaanite identity were put in unusual surroundings for months: extreme isolation, high, remote desert mountains, dangerous and hard work.

There was nothing in the area of the mines to divert their attention — except hundreds of hieroglyphic pictures inscribed on the rocks.

... The Egyptian pictorial script was the necessary tool for the invention of the alphabet.

The Egyptian signs presented the inventor with the hardware for his invention: the icons, the small pictures that he could easily recognize and identify.

Without this basic material, which he utilized in a completely innovative way, the invention would probably not have taken place.

1.

Note: Wikipedia, s.v. Proto-Sinaitic script,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Sinaitic_script#Discovery (accessed ...),

Discovery.

2.

Note: Ben Haring, Ancient Egypt and the earliest known stages of alphabetic writing,

in Understanding Relations Between Scripts II: Early Alphabets, ed. Philip J. Boyes and Philippa M. Steele (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2020), https://www.academia.edu/41166286/Understanding_Relations_Between_Scripts_II_Early_Alphabets (accessed ...),

p. 54.

3. Note: Ibid., p. 54, n. 6.

4.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, The Advantage of Cultural Periphery: The Invention of the Alphabet in Sinai (circa 1840 B.C.E),

in Culture Contacts and the Making of Cultures: Papers in Homage to Itamar Even-Zohar, ed. Rakefat Sela-Sheffy and Gideon Toury (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University / Unit of Culture Research, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/37555692/2011_The_Advantage_of_Cultural_Periphery_The_Invention_of_the_Alphabet_in_Sinai_circa_1840_B_C_E_In_Culture_Contacts_and_the_Making_of_Cultures_Papers_in_Homage_to_Itamar_Even_Zohar_Eds_R_Sela_Sheffy_and_G_Toury_Tel_Aviv_Tel_Aviv_University_Unit_of_Culture_Research_251_316 [pp. 251–316] (accessed ...),

pp. 264-265, 267.

Sinai 345 (17th-16th Century BCE, ca. 1700-1500)

|

Sinai 345 Figure; Trustees of the British Museum. Source: The British Museum.1 |

Sinai 345 Inscriptions; Alan H. Gardiner and T. Eric Peet. Source: Haring (2020).2 |

|

|

Transliteration source: ???? (????).3

| Transcription | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

[?] 𐤇 𐤍 ð 𐤍 𐤆 𐤋 𐤁 𐤏 𐤋 𐤕 𐤌 𐤀 𐤄 𐤁 𐤏 𐤋 𐤕 ? [?] |

Left Side [no more than 1 letter] ḥ̊ ṅ ð ṅ z l b ʿ l t Right Side m ʾ h b ʿ l̇ ṫ [1 or 2 letters] |

Transliteration source: Hamilton (2006).3

(Hamilton (2006):

ẋ supralinear dot indicates a damaged but certain reading;

x̊ supralinear circle indicates a very damaged or uncertain reading;

<> angular brackets indicate a correction or a secondary hand.

4)

Notes

Hamilton (2006):

Poorly executed but clear Egyptian inscription mry ḥtḥr mfk3t,

5beloved of Hathor, [lady of] turquoise

on its right shoulder.

Goldwasser (2010):

Sir Alan Gardiner...noticed a group of four signs that was frequently repeated in these unusual inscriptions.

Gardiner correctly identified the repetitive group of signs as a series of four letters in an alphabetic script that represented a word in a Canaanite language:

b-‘-l-t, vocalized as Baalat, “the Mistress.”

Gardiner suggested that Baalat was the Canaanite appellation for Hathor, the goddess of the turquoise mines.

... An important key to the decipherment [of the Serabit inscriptions] was a unique bilingual inscription [Sinai 345].

It is inscribed on a small sphinx from the temple and features a short inscription in what appears to be parallel texts in Egyptian and in the new script.

The Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription on the sphinx reads: “The beloved of Hathor, the mistress of turquoise.”

The text in the strange script, now identified as a Canaanite text, reads:

m-’-h (b) B-‘-l-t, “The beloved of Baalat.”

Each of the critical letters in the word Baalat is a picture—a house, an eye, an ox goad and a cross.

Gardiner correctly saw that each pictograph has a single acrophonic value:

The picture stands not for the depicted word but only for its initial sound.

Thus the pictograph bêt, “house,” drawn as the four walls of a dwelling represents only the initial consonant b.

... Each sign in this script stands for one consonant in the language.

6

Hamilton (2006):

ca. 1700-1500 B.C.

7

1.

Images: The Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number EA41748,

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA41748 (accessed ...).

2.

Drawings: Ben Haring, Ancient Egypt and the earliest known stages of alphabetic writing,

in Understanding Relations Between Scripts II: Early Alphabets, ed. Philip J. Boyes and Philippa M. Steele (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2020), https://www.academia.edu/41166286/Understanding_Relations_Between_Scripts_II_Early_Alphabets (accessed ...),

p. 55, Figure 4.1: Hieroglyphic and Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions on sphinx BM EA 41748 from Serabit el-Khadim. Facsimiles from Gardiner and Peet 1952, pl. lxxxii, no. 345. The chalk filling of the inscriptions is modern.

3. Transliteration: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,5.pdf [pp. 266-338] (accessed ...), p. 334.

4. Note: Ibid., p. 323.

5. Note: Ibid., p. 334.

6.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, How the Alphabet was Born from Hieroglyphs,

Biblical Archaeology Review [BAR] (Biblical Archaeology Society [BAS]) 36:2 (March/April 2010),

https://www.academia.edu/6916402/Goldwasser_O_2010_How_the_Alphabet_was_Born_from_Hieroglyphs_Biblical_Archaeology_Review_36_2_March_April_40_53_Award_Best_of_BAR_award_for_2009_2010_Discussion_with_Anson_Rainey_http_www_bib_arch_org_scholars_study_alphabet_asp_ [pp. 38-51] (accessed ...),

pp. 41-42.

7. Note: Ibid.

Sinai 346 (19th-18th Century BCE, ca. 1850-1700)

|

Sinai 346 Figure; Flinders Petrie. Source: Petrie (1906).1 |

Sinai 346, Right; Hubert Grimme. Source: Grimme (1923).2 |

Sinai 346, Right Side; Orly Goldwasser. Source: Goldwasser (2011).5 |

|

Sinai 346, Top; Orly Goldwasser. Source: Goldwasser (2011).3 |

Sinai 346, Front; Orly Goldwasser. Source: Goldwasser (2011).4 |

Sinai 346, Right Side, Direction of Reading; Orly Goldwasser. Source: Goldwasser (2011).6 |

| Transcription | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

𐤆 𐤍𐤎𐤀𐤕 𐤌𐤓𐤏𐤕 𐤋𐤁𐤏𐤋𐤕 𐤏𐤋 𐤍𐤏𐤌 𐤌𐤕 𐤏𐤋 𐤍𐤏𐤌 𐤓𐤁 𐤍𐤒𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤔 |

(1) z nsʾt mrʿt [top right] (3) lbʿlt [front] (2) ʿl nʿm mt [top left] (4) ʿl nʿm rb nqbn mš [right side] |

His (Moses') wife presented this to Baalt (Hathor) on behalf of her husband on behalf of the Chief of Miners, Moses |

Transliteration and translation source: Krahmalkov (2017).7

(Krahmalkov (2017):

The inscription consists of four lexical segments which, for the sake of reference, are designated by number as follows: on the front, two parallel columns, (1) a right column and (2) a left column, and beneath them, (3) a horizontal line; on the right side, (4) a single column.

... Translators of the inscription disagree about the proper sequencing of these four segments, with the inevitable result that their translations differ substantially from one another.

8)

| Transcription | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

𐤏 𐤋 𐤍 [𐤏 𐤌 ?] 𐤌 𐤕 𐤋 𐤁 𐤏 𐤋 𐤕 ð 𐤋 𐤃 40? 𐤌 𐤓 𐤏 𐤕 | 𐤏 𐤋 𐤍 𐤏 𐤌 𐤓 𐤁 𐤍 𐤒 𐤁 𐤍 |

346a ʿ l ṅ [ʿ m plus 1 letter] m t l b ʿ l t [top left and front] ð l d 40̊? m r ʿ t | [top right] 346b ʿ l n ʿ m ṙ b n q b n [right side] |

Transliteration source: Hamilton (2006):

346a: vertical column on the left turning into a left to right-horizontal line; a second vertical column on the right.

346b: vertical column turning into a boustrophedon quadrant of letters.9

(Hamilton (2006):

ẋ supralinear dot indicates a damaged but certain reading;

x̊ supralinear circle indicates a very damaged or uncertain reading;

<> angular brackets indicate a correction or a secondary hand.

10)

Notes

Goldwasser (2011):

[As one evidence that the inventors of the Canaanite alphabetic script in Sinai were illiterate,] in most [of the Sinaitic] inscriptions with more than one word...the direction of writing can be very confused.

... In [Sinai 346] one can follow the

11

(Goldwasser (2016):

winding road

of [the statuette's owner's] inscription on the right side of the statue.Sinai alphabetic inscription no. 349...is the only Proto-Sinaitic inscription in which the writer made the effort to write between baselines imitating more closely the Egyptian stelae tradition.

12)

Wilson-Wright (2017):

Beginning in in 1905 and continuing until the 2000s, excavators uncovered a series of

early alphabetic inscriptions associated with the Egyptian turquoise mining installation at Serabit

el-Khadem in the Sinai desert. Scholars quickly identified the language of these inscriptions as

Semitic due to the presence of marquee Semitic words like

13lady

(BʿLT), chief

(RB), and miner

(NQB),

but a full decipherment has remained elusive.

Krahmalkov (2017):

After having cleared the debris at the entrance to the hall of the grotto-shrine of Ptah in the Temple of Hathor on Mt Serabit el-Khadem in SW Sinai, W.M. Flinders Petrie discovered a small cuboid statue of a man whom the dedicatory inscription (Sinai 346) identifies as the Chief of Miners, Moses (MŠ, Mashe/ Moshe), the son of Mahub-Baalt of Gath, the leader of a copper and turquoise mining community that flourished c. 1300-1250 BCE.

Moses the Miner, as he calls himself in Sinai 351, is well attested in the Serabit inscriptions, which are the personal monuments of the members of his family, his father, Mahub-Baalt, his two brothers, Shubna-Sur and Shesha and Shesha’s wife, Arakht, and of course himself.

14

Wilson-Wright (2017):

The Sinaitic inscriptions do not contain the name Moses.

... The two letter sequence that Krahmalkov transcribes as MŠ appears in five of the Sinaitic inscriptions: Sinai 349, Sinai 351, Sinai 353, Sinai 360, and Sinai 361.

[Wilson-Wright (2017):

16Krahmalkov also identifies MŠ in Sinai 346, but I could not find these letters in the images available to me.

15]

Already in 1928 Romain Butin identified MŠ with the name Moses.

... Subsequent scholars have not followed Butin’s identification.

Following Butin’s 1928 article, epigraphers recognized that the Sinaitic script contained at least four more letters than the Phoenician alphabet.

These extra letters represented sounds that were lost in Phoenician, but were preserved in other Semitic languages.

... One of these letters was Ṯ, which represented the sound found at the beginning of the English word thin.

The letter that Butin and Krahmalkov transcribe as Š, no doubt based on its visual resemblance to the later Phoenician Š, is actually a Ṯ.

... the Sinaitic inscriptions do not contain the name Moses, but it is theoretically possible that they record the exploits of a man named Māṯ.

Hamilton (2006):

ca. 1850-1700 B.C.

17

1. Image: W. M. Flinders Petrie, Researches in Sinai (London: John Murray, 1906), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044019341643&view=1up&seq=307 (accessed ...), p. 131, Fig. 138: Sandstone fiture, foreign work and inscription.

2. Image: Hubert Grimme, Althebräische Inschriften vom Sinai: Alphabet, Textliches, Sprachliches mit Folgerungen (Hannover: Orient-Buchhandlung Heinz Lafaire, 1923), https://archive.org/stream/althebrischein00grimuoft?ref=ol#page/n115/mode/2up (accessed ...), Tafel 8: Männliche Hockerstatue, Nr. 346 (2). Rechte Seite.

3.

Drawing: Orly Goldwasser, The Advantage of Cultural Periphery: The Invention of the Alphabet in Sinai (circa 1840 B.C.E),

in Culture Contacts and the Making of Cultures: Papers in Homage to Itamar Even-Zohar, ed. Rakefat Sela-Sheffy and Gideon Toury (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University / Unit of Culture Research, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/37555692/2011_The_Advantage_of_Cultural_Periphery_The_Invention_of_the_Alphabet_in_Sinai_circa_1840_B_C_E_In_Culture_Contacts_and_the_Making_of_Cultures_Papers_in_Homage_to_Itamar_Even_Zohar_Eds_R_Sela_Sheffy_and_G_Toury_Tel_Aviv_Tel_Aviv_University_Unit_of_Culture_Research_251_316 [pp. 251–316] (accessed ...),

p. 256, The Statue of N-ʿ-m chief miner

/ Sinai 346 top and front (after Hamilton 2006: Fig. A9).

4. Drawing: Ibid.

5. Drawing: Ibid., p. 312, Fig. 9a: The Statue of N-ʿ-m arrangement of words (after Sinai I, Temple, 346b, right side).

6. Drawing: Ibid., p. 313, Fig. 9b: The Statue of N-ʿ-m direction of reading (after Sinai I, Temple, 346b, right side).

7.

Transliteration and translation: Charles R. Krahmalkov, The Chief of Miners, Moses (Sinai 346, c. 1250 BCE),

Université catholique de Louvain BABELAO 6 (2017), https://cdn.uclouvain.be/groups/cms-editors-ciol/babelao/2017/03-Ch._R._Krahmalkov%2C_The_Chief_of_Miners%2C_Moses_%28Sinai_346%29.pdf [pp. 63-74] (accessed ...),

p. 67.

8. Note: Krahmalkov, pp. 65-66.

9. Transliteration: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,5.pdf [pp. 266-338] (accessed ...), p. 336.

10. Note: Hamilton, p. 323.

11. Note: Goldwasser, p. 272.

12.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, From Iconic to Linear – The Egyptian Scribes of Lachish and the Modification of the Early Alphabet in the Late Bronze Age,

in Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies presented to Benjamin Sass, ed. Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin and Thomas Römer (Paris: Van Dieren, 2016), https://www.academia.edu/30713970/_From_Iconic_to_Linear_The_Egyptian_Scribes_of_Lachish_and_the_Modification_of_the_Early_Alphabet_in_the_Late_Bronze_Age_In_Alphabets_Texts_and_Artefacts_in_the_Ancient_Near_East_Studies_presented_to_Benjamin_Sass_eds_I_Finkelstein_C_Robin_and_T_Römer_Paris_Van_Dieren_2016 [pp. 118–160] (accessed ...),

p. 147.

13.

Note: Aren M. Wilson-Wright, Wandering in the Desert?: A Review of Charles R. Krahmalkov’s

, The Bible and Interpretation (University of Arizona), March 2017, https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/docs/Review%20of%20Krahmalkov%203_0.pdf (accessed ...),

p. 2.The Chief of Miners Mashe/Moshe, the Historical Moses

14. Note: Krahmalkov, p. 64.

15. Note: Wilson-Wright, p. 2, n. 3.

16. Note: Ibid., pp. 2-4.

17. Note: Hamilton, p. 336.

Sinai 347-355

Alan H. Gardiner and T. Eric Peet. Source: Gardiner, Peet (1917).1

Notes

Gardiner, Peet (1917):

The consecutive numbers 1 to 355 are those by which, the editors hope, the inscriptions [of Sinai] will henceforth be known; for purposes of reference

2Sinai 147

ought to prove an adequate mode of quotation.

The principles of classification followed by us must here be explained.

The main division is between Egyptian and non-Egyptian inscriptions: the latter (345-355) consist of no more than eleven monuments exhibiting the new script discussed in Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. iii, pp. 1-21.

1. Drawings: Alan H. Gardiner and T. Eric Peet, The Inscriptions of Sinai: Part I; Introduction and Plates (London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1917), https://archive.org/details/EXCMEM36/page/n106/mode/1up (accessed ...), Plates LXXXII-LXXXIII.

2. Note: Ibid., p. 4.

Sinai 356-

Hamilton (2006): The Proto-Canaanite Inscriptions from the Sinai: Sinai 345-347, (348?), 349-354, (355?), 356-365, (366?), 367, 374-375, 375a, 375c, 376-380, 5271

1. Note: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,W.Sem%20Alphabet,1.pdf [pp. 1-64] (accessed ...), pp. xiv-xv, Contents.

Wadi el-Hol Inscriptions [1999] (19th-18th Century BCE, ca. 1850-1700)

Wadi el-Hol Inscription No. 1; West Semitic Research Project. Source: Wayback Machine.1

Wadi el-Hol Inscription No. 1; Marilyn Lundberg. Source: Wikimedia Commons.2

|

|

|

Wadi el-Hol Inscription No. 2; West Semitic Research Project. Source: Wayback Machine.3 |

Wadi el-Hol Inscription No. 2; Marilyn Lundberg. Source: Wikimedia Commons.4 |

| Transcription | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

𐤓 𐤁 <𐤉?> 𐤋 𐤍 𐤌 𐤍 𐤄 𐤍 𐤐 θ/𐤔 𐤄 𐤀 𐤏/𐤔 ḫ 𐤓 𐤌 𐤊/θ/ǵ 𐤕 𐤓 𐤄 𐤏 𐤅 𐤕 𐤉 𐤐 𐤊/θ/ǵ 𐤀 𐤋 |

Wadi el-Ḥol Text 1 r b <ẙ?> l n m n h n p θ̇/ṧ h ʾ ʿ/š ḫ ṙ Wadi el-Ḥol Text 2 m k̊/θ̊/ǵ̊ t r h ʿ w t y p k̊/θ̊/ǵ̊ ʾ l |

Transliteration source, Hamilton (2006):

Lines below the bêt [in text 1] appear to be a

5

(Hamilton (2006):

curved palm

type of yôd....

This could be a subscript correction of rb, great one, chief

to rby, my great one, my chief.

But one would need to examine the original to be sure these were intentional and not just random marks (as taken in the editio princeps).ẋ supralinear dot indicates a damaged but certain reading;

x̊ supralinear circle indicates a very damaged or uncertain reading;

<> angular brackets indicate a correction or a secondary hand.

6)

Notes

Haring (2015):

Two inscriptions in a writing very similar to the Sinai texts were discovered in 1999 in the Wadi el-Hol, in the desert to the northwest of Luxor.

The two short sequences (together showing fourteen different signs) have so far not yielded any satisfactory translation, but the characters are so similar to those of the Sinai inscriptions that they must be related.

6

Wikipedia:

The inscriptions are graphically very similar to the Serabit inscriptions, but show a greater hieroglyphic influence, such as a glyph for a man....

Goldwasser (2011):

The main paleographic difference between the two early examples of the alphabet — the inscriptions in Sinai and the inscriptions in Wadi el-Ḥôl in Egypt, lies in the execution of two letters — bêt and mem.

7

Goldwasser (2016):

Iconic Proto-Canaanite Inscriptions in Egypt—Middle Bronze Age and Late Bronze II...Wadi el-Hôl Inscriptions....

8

Hamilton (2006):

ca. 1850-1700 B.C.

9

1.

Image: Internet Archive Wayback Machine, http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/information/wadi_el_hol/inscr1.jpg,

https://web.archive.org/web/20160303184024/http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/information/wadi_el_hol/inscr1.jpg (accessed ...).

2.

Drawing: Wikimedia Commons, Wadi el-Hol inscriptions I drawing,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wadi_el-Hol_inscriptions_I_drawing.jpg (accessed ...), Drawing by Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research.

3.

Image: Internet Archive Wayback Machine, http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/information/wadi_el_hol/inscr2.jpg,

https://web.archive.org/web/20160303211918/http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/information/wadi_el_hol/inscr2.jpg (accessed ...).

4.

Drawing: Wikimedia Commons, Wadi el-Hol inscriptions II drawing,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wadi_el-Hol_inscriptions_II_drawing.jpg (accessed ...), Drawing by Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research.

5. Transliteration: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,5.pdf [pp. 266-338] (accessed ...), pp. 323, 325, 328.

6.

Ben Haring, The Sinai Alphabet: Current State of Research,

in Proceedings of the Multidisciplinary Conference on the Sinai Desert (Cairo: Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo, 2015), https://www.academia.edu/12439545/The_Sinai_Alphabet_Current_State_of_Research_in_R_E_de_Jong_T_C_van_Gool_and_C_Moors_eds_Proceedings_of_the_Multidisciplinary_Conference_on_the_Sinai_Desert_Cairo_2015_18_32 (accessed ...),

p. 24.

7.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, The Advantage of Cultural Periphery: The Invention of the Alphabet in Sinai (circa 1840 B.C.E),

in Culture Contacts and the Making of Cultures: Papers in Homage to Itamar Even-Zohar, ed. Rakefat Sela-Sheffy and Gideon Toury (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University / Unit of Culture Research, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/37555692/2011_The_Advantage_of_Cultural_Periphery_The_Invention_of_the_Alphabet_in_Sinai_circa_1840_B_C_E_In_Culture_Contacts_and_the_Making_of_Cultures_Papers_in_Homage_to_Itamar_Even_Zohar_Eds_R_Sela_Sheffy_and_G_Toury_Tel_Aviv_Tel_Aviv_University_Unit_of_Culture_Research_251_316 [pp. 251–316] (accessed ...),

p. 294

8.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, From Iconic to Linea – The Egyptian Scribes of Lachish and the Modification of the Early Alphabet in the Late Bronze Age,

in Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies presented to Benjamin Sass, ed. Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin and Thomas Römer (Paris: Van Dieren, 2016), https://www.academia.edu/30713970/_From_Iconic_to_Linear_The_Egyptian_Scribes_of_Lachish_and_the_Modification_of_the_Early_Alphabet_in_the_Late_Bronze_Age_In_Alphabets_Texts_and_Artefacts_in_the_Ancient_Near_East_Studies_presented_to_Benjamin_Sass_eds_I_Finkelstein_C_Robin_and_T_Römer_Paris_Van_Dieren_2016 [pp. 118–160] (accessed ...),

p. 136.

9. Note: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,5.pdf [pp. 266-338] (accessed ...), pp. 325, 328.

Lahun Heddle Jack [1890] (19th-14th Century BCE)

Lahun Heddle Jack; Trustees of the British Museum. Source: The British Museum.1

|

|

| ||

|

Lahun Heddle Jack Inscription; Carla Gallorini. Source: Gallorini (2009).2 |

Egyptian Heddle Jacks; University College London. Source: Digital Egypt for Universities3. |

| Transcription | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

𐤀𐤇𐤉𐤈𐤁 𐤀𐤇𐤉𐤑𐤁 𐤀𐤃𐤏𐤑𐤁 |

ʾḥyṭb ʾḥyṣb ʾdʿṣb |

Transliteration source: Haring (2020):

The inscription has been read as ʾḥyṭb (Eisler 1919, 125 and 172), ʾḥyṣb (Dijkstra 1990, also allowing for a dating as late as the fourteenth century) or ʾdʿṣb (Hamilton 2006, 331: eighteenth–seventeenth century).

4

Hamilton (2006):

When in use, with its point down, the text incised around this heddle jack reads from right to left.

This was likely intended as the primary direction of reading to judge from the archaic stances of ʾālep and ṣādê when viewed from that direction.

... The incision of the owner’s name was likely intended to differentiate this heddle jack from others.

5

Colless (2020):

The second sign appears to be Het (H̱ or H.).... However, there is a small projection at the top left corner, indicating a doorpost, and defining the character as a door, Dalt, hence D (so Hamilton).

6

| Transcription | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

𐤆𐤕𐤐𐤃𐤋 |

ztpdl |

Transliteration source: Colless (2020):

The Heddle Jack inscription is regularly exhibited irregularly [upside down] to achieve a proto-alphabetic text.

... The marks above the first letter...Hamilton (2007: 29) suggests that a probable interpretation of

7this deeply incised horizontal line is as a separation mark signaling the end of the owner's name

; but he is at a loss to explain the three shorter, shallower nicks

.

Let us suppose that the longer incision at the top serves to indicate the start of the text.

The two parallel lines are known to be the letter Dh (D) in the proto-alphabet, and is often found as saying This (is)

at the beginning of Sinai inscriptions at the turquoise mines.

... Finally, we can no longer see the ox-head, and I doubt that we can ever find an `Alep or Alpha with a right angle.

... Speaking for myself, I would like it to say: This is a heddle jack.

Hamilton (2006):

The only surprise from a paleographic perspective is the presence of a linear A-form of ʾālep in an inscription that would be dated to ca. 1850-1700 B.C....

Yet compare a similar but atypical form of the hieroglyphic antecedent of that letter, F1, on a rock inscription from Nubia dating to the early Middle Kingdom which provides an analogy for the parallel development of this linear form in early alphabetic scripts.

See also the A-forms of ʾālep, with a different stance, that occur on the front of the Shechem Plaque....

There is thus nothing in the paleography of the Lahun Heddle Jack that precludes its assignment to late in the Middle Kingdom.

8

Notes

Burlingame (2019):

The Lahun heddle jack, which, though known for some time, was more recently rediscovered in the British Museum.

9

Haring (2020):

The wooden heddle jack found during [W.M.F.] Petrie’s excavations at El-Lahun (Kahun) is inscribed with linear signs believed by many scholars to be alphabetic.

10

Goldwasser (2006):

[Benjamin] Sass is of the opinion that

11the signs do not resemble Proto-Canaanite letters of any date, let alone the earliest examples.

Sparks (2004):

Textile production is one of the crafts in Egypt that used a high proportion of Asiatic personnel, often acquired as prisoners of war.

A wooden heddle jack from Lahun bore a proto-Canaanite inscription, suggesting just such an owner.

12

Colless (2020):

Its fir-tree wood is not native to the Nile Valley region, so it must have been brought from elsewhere.

13

Dijkstra (1991):

On the basis of the archeological evidence either a 16th century date, or a 14th century date are acceptable.

This means that the Kahun inscription is datable within the range of established alphabetic origins, i.e.,

between the scarce inscriptions of the outgoing Middle Bronze period like the Nāgīlā sherd, Lachish dagger, Shechem plaque and probably the Gezer sherd

and the better attested Proto-Canaanite inscriptions of the Late Bronze Age script of the 13th century B.C.

14

Digital Egypt for Universities:

A number of such jacks were preserved at Lahun, dating to the late Middle Kingdom, about 1850-1750 BC.

15

Hamilton (2006):

Found at Lahun/el-Lahun, in the town area sometimes referred to as

16Kahun.

... ca. 1850-1700 B.C.

1.

Image: The Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number EA70881,

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA70881 (accessed ...).

2.

Drawing: Carla Gallorini, Incised Marks on Pottery and Other Objects From Kahun,

in Pictograms or Pseudo-Script? Non-Textual Identity Marks in Practical Use in Ancient Egypt and Elsewhere, ed. B.J.J. Haring and O.E. Kaper (2009), https://www.academia.edu/435313/Incised_Marks_on_Pottery_and_Other_Objects_From_Kahun [pp. 107-142] (accessed ...), p. 119, Fig. 4: Wooden heddle-jack EA 70881 (scale 1:4).

3.

Image: Digital Egypt for Universities, Textile production and clothing: Technology and tools in ancient Egypt,

(University College London) 2003, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/textil/tools.html, LOOMS and weaving.

4.

Transliteration: Ben Haring, Ancient Egypt and the earliest known stages of alphabetic writing,

in Understanding Relations Between Scripts II: Early Alphabets, ed. Philip J. Boyes and Philippa M. Steele (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2020), https://www.academia.edu/41166286/Understanding_Relations_Between_Scripts_II_Early_Alphabets (accessed ...),

p. 60.

5. Note: Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2006), http://library.mibckerala.org/lms_frame/eBook/Hamilton,5.pdf [pp. 266-338] (accessed ...), p. 331.

6.

Note: Brian E. Colless, Lahun Syllabic Heddle Jack,

CRYPTCRACKER, 12 August 2020, http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2020/08/lahun-syllabic-heddle-jack.html (accessed ...).

7. Note: Ibid.

8. Note: Hamilton, p. 297.

9.

Note: Andrew Burlingame, Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Recent Developments and Future Directions,

Bibliotheca Orientalis LXXVI N. 1-2 (January-April 2019), https://www.academia.edu/40309512/Writing_and_Literacy_in_the_World_of_Ancient_Israel_Recent_Developments_and_Future_Directions (accessed ...),

p. 49, n. 8.

10. Note: Ben Haring, p. 59.

11.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, Canaanites Reading Hieroglyphs: Horus is Hathor? — The Invention of the Alphabet in Sinai,

Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant 16 (2006), https://www.academia.edu/6465779/Goldwasser_O_2006_Canaanites_Reading_Hieroglyphs_Part_I_Horus_is_Hathor_Part_II_The_Invention_of_the_Alphabet_in_Sinai_Ägypten_und_Levante_16_121_160 [pp. 121-160] (accessed ...),

p. 132, n. 64.

12.

Note: Rachael Sparks, Canaan in Egypt: Archaeological Evidence for a Social Phenomenon,

in Invention and Innovation: The Social Context of Technological Change 2: Egypt, the Aegean and the Near East, 1650-1150 B.C., ed. Janine Bourriau and Jacke Phillips (Oxbow Books, 2004), https://www.academia.edu/401045/Canaan_In_Egypt_Archaeological_Evidence_for_a_Social_Phenomenon [pp. 27-56] (accessed ...),

p. 43.

13. Note: Colless.

14.

Note: Meindert Dijkstra, The So-called ʾĂḥīṭūb-Inscription from Kahun (Egypt),

Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins [ZDPV] 106 (1991), https://www.academia.edu/34809620/M_Dijkstra_The_So_called_Ahitub_Inscription_from_Kahun_Egypt_ZDPV_106_1991_51_56 [pp. 51-56] (accessed ...),

p. 53.

15. Note: Digital Egypt for Universities.

16. Note: Hamilton, p. 331.

Valley of the Queens Ostracon [????] (13th-12th Century BCE)

|

Valley of the Queens Ostracon; Benjamin Sass. Source: Goldwasser (2016).1 |

Valley of the Queens Ostracon; Joseph Leibovich. Source: Goldwasser (2011).2 |

| Transcription | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

𐤀𐤌𐤄𐤕 𐤀𐤔𐤕 |

ʾmht ʾšt |

maidservants women |

Transliteration and translation source, Colless (2010):

My reading for the two lines (right to left): ' M H T (maidservants), ' Sh T (women).

3

Notes

Colless (2010):

Benjamin Sass...disallows this as proto-alphabetic, contra [J.] Leibovitch, [W. F.] Albright, [A.] van den Branden, and myself.

4

Morenz (2018):

I would suggest reading the bottom line [of the ostracon from the Valley of the Queens] as [Egyptian] hieratic script corresponding to the top line containing alphabetic letters.

... For any attempts of interpretation, we should consider the layout and the framing lines indicating a certain demarcation between the two distinctly different types of writing on the ostracon.

5

Goldwasser (2016):

Middle Bronze Age and Late Bronze II ... Valley of the Queens Alphabetic (?) Ostracon (New Kingdom) ...

The upper part of this little ostracon shows four signs that may be identified as iconic Proto-Canaanite.

... The lower part of this ostracon seems to present signs written, again, in a “non-Egyptian” style but not fitting any known letters of the Canaanite alphabet.

6

[Morenz (2018):

In contrast (to Orly Goldwasser) I’d rather understand the three signs to be distinctly hieratic.

7]

Morenz (2018):

We notice...correspondences between the signs in the two lines on this ostracon.

... The scribe chose rather similar hieratic forms as equivalents to the alphabet letters.

... The original alphabet letters and the earliest examples known from Serabit el Khadim were clearly based on other hieroglyphic prototypes, including, in many cases an acrophonic derivation within the Semitic language.

Thus, we can expect a reinterpretation of the primary alphabet letters within the horizon of a scribe trained in Egyptian New Kingdom hieratic script.

... We might assume the scribe to have been more familiar with Hieratic than alphabetic writing, and this assumption fits nicely with the observation that the scribe of this ostracon appears to have chosen hieratic signs with formal similarities to the alphabet letters.

... This ostracon...provides...evidence for the question of how Egyptian scribes in the New Kingdom approached foreign writing systems to understand and probably learn them.

... The interest of the Egyptian scribes in alphabetic writing might have been fostered more by intellectual curiosity and probably a more individual approach to a certain foreign writing system.

... The ostracon...is another important document for the usage of alphabetic writing during the New Kingdom/Late Bronze Age...from 13/12 century BCE.

8

1.

Image: Orly Goldwasser, From Iconic to Linear –The Egyptian Scribes of Lachish and the Modification of the Early Alphabet in the Late Bronze Age,

in Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies presented to Benjamin Sass, ed. Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin and Thomas Römer (Paris: Van Dieren, 2016), https://www.academia.edu/30713970/_From_Iconic_to_Linear_The_Egyptian_Scribes_of_Lachish_and_the_Modification_of_the_Early_Alphabet_in_the_Late_Bronze_Age_In_Alphabets_Texts_and_Artefacts_in_the_Ancient_Near_East_Studies_presented_to_Benjamin_Sass_eds_I_Finkelstein_C_Robin_and_T_Römer_Paris_Van_Dieren_2016 [pp. 118–160] (accessed ...),

p. 140, Figure 14: Valley of the Queens alphabetic(?) ostracon. (After Sass 1988: Fig. 286.)

2.

Drawing: Orly Goldwasser, The Advantage of Cultural Periphery: The Invention of the Alphabet in Sinai (circa 1840 B.C.E),

in Culture Contacts and the Making of Cultures: Papers in Homage to Itamar Even-Zohar, ed. Rakefat Sela-Sheffy and Gideon Toury (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University/ Unit of Culture Research, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/37555692/2011_The_Advantage_of_Cultural_Periphery_The_Invention_of_the_Alphabet_in_Sinai_circa_1840_B_C_E_In_Culture_Contacts_and_the_Making_of_Cultures_Papers_in_Homage_to_Itamar_Even_Zohar_Eds_R_Sela_Sheffy_and_G_Toury_Tel_Aviv_Tel_Aviv_University_Unit_of_Culture_Research_251_316 [pp. 251–316] (accessed ...),

p. 309, Fig. 3b: Valley of the Queens ostracon (after Leibovich 1940).

3.

Transliteration and translation: Brian E. Colless, Timna Inscriptions,

CRYPTCRACKER, 08 April 2010, http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2010/04/timna-inscriptions-copper-mines-at.html (accessed ...).

4. Note: Ibid.

5.

Note: Ludwig D. Morenz, Early Alphabetic Writing and Its Correspondence to New Kingdom Hieratic Considering a BI–graphic Sequence of Signs on an Ostracon from the New Kingdom,

Abgadiyat: Journal of Arabic Calligraphy (Brill) 13:1 (Sep 2018), https://journals.ekb.eg/article_54831_ba016a8087499f2dbbd24c8c4b6c167d.pdf [pp. 14–18] (accessed ...),

p. 15.

6.

Note: Orly Goldwasser, From Iconic to Linear –The Egyptian Scribes of Lachish and the Modification of the Early Alphabet in the Late Bronze Age,

in Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies presented to Benjamin Sass, ed. Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin and Thomas Römer (Paris: Van Dieren, 2016), https://www.academia.edu/30713970/_From_Iconic_to_Linear_The_Egyptian_Scribes_of_Lachish_and_the_Modification_of_the_Early_Alphabet_in_the_Late_Bronze_Age_In_Alphabets_Texts_and_Artefacts_in_the_Ancient_Near_East_Studies_presented_to_Benjamin_Sass_eds_I_Finkelstein_C_Robin_and_T_Römer_Paris_Van_Dieren_2016 [pp. 118–160] (accessed ...),

pp. 136, 139.

7. Note: Morenz, p. 17, n. 5.

8. Note: Ibid., pp. 15-16.

Proto-Sinaitic Fonts

| Phoenician / Paleo-Hebrew | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾ | b | g | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | l | m | n | s | ʿ | p | ṣ | q | r | š | t | |||||

| 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | |||||

| Proto-Sinaitic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colless (2014)* | A | B | Pg | D | - | H | W | Z | X | Y | KCJ | L | M | N | S | [ | - | Q | R{ | FV | - | T | ||||

| a | bã | G@ | d | - | h | w | z | xå | á | j | y | kc | l | m | n | sà | - | p | ä | q | r | vf | - | t | ||

| A | B | Pg | D | - | H | W | Z | X | Y | KCJ | L | M | N | S | [ | Q | R{ | FV | - | T | ||||||

| a | bã | G@ | d | - | h | w | z | xå | á | j | y | kc | l | m | n | sà | - | p | ä | q | r | vf | - | t | ||

| Albright (1969)† | A | B | G | D | C | H | W | - | I | X | - | Y | K | LJ | M | N | - | E | F | P | S | Q | R | V | T | |

| a | b | g | d | c | h | w | - | i | x | - | y | k | lj | m | nf | - | e | p | s | q | r | t | v | |||

| A | B | G | D | C | H | W | - | I | X | - | Y | K | LJ | M | N | - | E | F | P | S | Q | R | V | T | ||

| a | b | g | d | c | h | w | - | i | x | - | y | k | lj | m | nf | - | e | p | s | q | r | t | v | |||

| Rejected Unicode Proposal (1998)‡ |  |

|

|

|

- |  |

|

|

|

- | - |  |

|

|

|

|

- |  |

- | - |  |

|

|

|

- |  |

* Colless: Chart of Alphabet Evolution.1 (Font: Protosinaitic 1 [Proto-Sinaitic 15.ttf] designed by Kris Udd 2006.)

† Albright: Schematic Table of Proto-Sinaitic Characters.2 (Font: ProtoSinatic [proto-si.ttf] designed by Kyle Pope 2001.)

‡ Everson: http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n1688/n1688.htm3 and http://www.unicode.org/L2/L1999/protosinaitic.pdf.

1. Brian E. Colless (2014), The Origin of the Alphabet: An Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis, http://www.academia.edu/12894458/The_origin_of_the_alphabet#page=103 (accessed 30 Dec 2018), Fig. 1. Chart of Alphabet Evolution, p. 103.

2. William Foxwell Albright (1969), The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and Their Decipherment, https://www.scribd.com/document/341115795/Albright-The-Proto-Sinaitic-Inscriptions-and-Their-Decipherment-1969#page=16 (accessed 30 Dec 2018), Fig. 1. Schematic Table of Proto-Sinaitic Characters, p. 10.

3. Michael Everson (1998), Proposal to encode Sinaitic in Plane 1 of ISO/IEC 10646-2, http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n1688/n1688.htm (accessed 30 Dec 2018).

Pandey, Anderson: Undeciphered Scripts in the Unicode Age: Challenges for encoding early writing systems of the Near East:

Possible correspondences between Proto-Sinaitic and Phoenician.

Jack Kilmon:

Certain Egyptian hieroglyphs such as mouth.gif (562 bytes) which was pronounced r'i meaning "mouth" became the pictograph for the sound of R with any vowel. The pictograph for "water" pronounced nu river.gif (1017 bytes)became the symbol for the consonantal sound of N. This practice of using a pictograph to stand for the first sound in the word it stood for is called acrophony and was the first step in the development of an ALPHABET or the "One Sign-One sound" system of writing....

The Egyptians [themselves] used the acrophones as a consonantal system along with their syllabic and idiographic system, therefore the alphabet was not yet born. The acrophonic principal of Egyptian clearly influenced Proto-Canaanite/Proto-Sinaitic around 1700 BC. Inscriptions found at the site of the ancient torquoise mines at Serabit-al-Khadim in the Sinai use less than 30 signs, definite evidence of a consonantal alphabet rather than a syllabic system.

Clay Model House

Image source: The Israel Museum.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Clay model house, 3,000-2,650 BCE

Rebuttal to encoding Proto-Sinaitic

Keown, REBUTTAL to “Final proposal for encoding the Phoenician script in the UCS”:

In a 1990 article in the journal Abr-Nahrain, Prof. Brian E. Colless makes the following observations about Proto-Sinaitic:

• only 1/3 of the letters can be deciphered with certainty

• there is “No set direction for the line of writing.”

J. Naveh observed: “it would be premature to state that the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions have been satisfactorily deciphered.”

Röllig, Comments on proposals for the Universal Multiple-Octed Coded Character Set:

It is absolutely superfluous to generate the characters of Proto-Sinatic inscriptions, as especially

in this case a high variability of characters is of the essence

:

The literature used by authors of character lists is mostly of a secondary nature.... Through this, of course,

mistakes have been added. Some of this literature is also clearly no longer up to date. From this

follows, furthermore, that sometimes character forms appear in these character lists that are not

correct or at least cannot be understood in this manner anymore today.... If they knew these variants, the authors should have noticed that their

undertaking was not very useful

Opposition to encoding Phoenician, Aramaic, and Hebrew as distinct character sets